Condenser mics are best known for their sound sensitivity, wide frequency response, and phantom power requirements, but what’s going on inside to give them that signature sound? Let’s take a closer look:

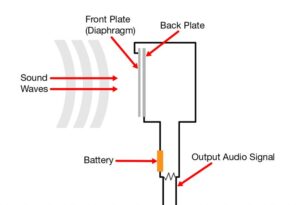

Condenser mics get their name from the “capacitor” inside that converts acoustic energy into an electrical signal (“condenser” is an old term for “capacitor”). The capacitor in a studio condenser microphone consists of two metal-surfaced plates suspended in very close proximity to each other with a voltage across them.

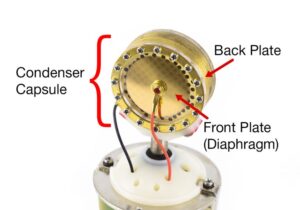

One of the metal plates is called a back plate, which is typically made of solid brass, and the other is called a diaphragm, made of very lightweight metal or in many cases gold-sputtered mylar. The capacitor is housed in what’s called a microphone capsule, and it can be plainly seen in entirety when you remove the microphone grille from most condenser mics.

The diaphragm detects subtle variations in air pressure, which make up the sound of the room, vocal, or instrument being recorded. As the sound waves vibrate the diaphragm, the varying distance between the diaphragm and the back plate causes the voltage across the capacitor to change. This voltage is the electrical signal, rapidly fluctuating to mimic the pattern of the original sound waves.

But before this signal can be heard over speakers, it needs to be boosted, because the voltage between the capacitor plates produces almost no current at all. So in order for a condenser microphone to work, it needs an external power source to amplify the signal. There’s a few different ways to do this:

In today’s studio environment, this is most often achieved using 48V Phantom Power, which is a 48-volt signal sent from a preamp or audio interface directly through the XLR cable to the microphone. (It’s called Phantom Power because of its a

bility to send a power supply through the same XLR cable that is transferring the audio signal.)

Amplification in condenser mics can also be done through a vacuum tube. A tube condenser microphone uses a vacuum tube to boost the signal from the capsule for proper recording and/or broadcasting. Tube microphones require more power than the standard 48V Phantom Power, and come with their own external power supply. Tube technology is the oldest way to amplify a microphone, but many musicians today still swear by the warm tones created with the heated-up tubes.

A third way you can power a microphone capacitor is through an “electret.” An ele

ctret is a permanently charged dielectric substance that can supply continuous power to a condenser capacitor, typically through an on-board battery. The electret material is applied as an ultra-thin film to either the back plate or the capsule diaphragm. Electret condenser microphones are most often found in smaller, portable microphones like lavalier mics, laptop mics, and cell phones.

Now that you have a little background on how condenser mics work, check out ours!